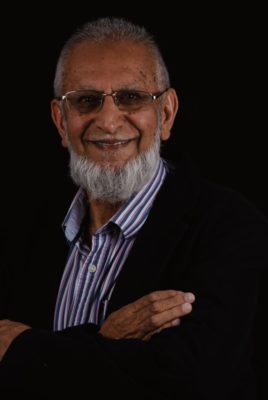

Rafik Gardee has a fascinating story to tell. Get It visits him to talk about practising as a medical doctor during apartheid, his years in Scotland and his eventual return to South Africa.

His life story starts with his grandfather, Mohammed Ismail Gardee, who moved to South Africa from India in 1908 and eventually settled in the White River area.

Mohammed was a philanthropist and involved in many community upliftment projects of which co-establishment of the Plaston Clinic was but one. The clinic, which served the black community for more than 50 years, closed when Themba Hospital was built in 1974.

Mohammed was a philanthropist and involved in many community upliftment projects of which co-establishment of the Plaston Clinic was but one. The clinic, which served the black community for more than 50 years, closed when Themba Hospital was built in 1974.

Rafik continued his grandfather’s legacy. After matriculating from the Johannesburg Indian High School, he studied medicine in Dublin, Ireland at the Royal College of Surgeons and returned to the Lowveld in 1970. In those times the increasingly oppressive apartheid laws dictated that non-white general practitioners could treat only non-whites. Sadly, the government clinics in rural areas were ill-equipped and resources were scarce.

He saw this as an opportunity to make a difference and established decentralised primary healthcare clinics within his area of practice in the Lowveld. These clinics provided essential healthcare for the then “undeserved, impoverished and disenfranchised non-white community”, marginalised by the apartheid regime.

“My team and I did not only diagnose and treat, but also initiated a unique childcare programme,” Rafik says. Every child was issued with a handheld clinic card that gave easy access to their health records. According to him, it was a first in South Africa and he is justifiably proud of what they achieved.

Rafik remembers the seven years spent in rural areas as exciting rather than frustrating, and he was well loved and respected. He tells how several boys were named after him – in those days black people tended to name children after people they cared for and respected. “One day I went on a house call and one of a group of boys asked me what I was doing there,” he laughs. “The boy’s mother came out of the house, klapped the youngster, and told him that he must love this doctor who delivered him in difficult circumstances, in a field near the house.”

The joy came to an end when his activities came under the attention of the authorities and his clinics were frequently raided. Rafik was compelled to leave South Africa and moved to Glasgow, Scotland where he completed his specialist training in public health medicine, with particular interest in the health of minority ethnic communities.

The joy came to an end when his activities came under the attention of the authorities and his clinics were frequently raided. Rafik was compelled to leave South Africa and moved to Glasgow, Scotland where he completed his specialist training in public health medicine, with particular interest in the health of minority ethnic communities.

He did not only advocate for better measures to overcome language barriers experienced by non-Scottish patients, but also for better opportunities for medical professionals of all ethnic groups. “We did not need special privileges, but special considerations based on differences in culture, religion and skin colour,” Rafik says. “Following our review of institutional racism within the Scottish NHS, the government acted by establishing a national resource centre for ethnic minority health which subsequently had quite a positive impact on the system.”

He obtained a master’s degree in public health and became a fellow of public health medicine at Glasgow University. He mentored nearly 3 000 postgrad students during his years overseas and has been a visiting professor at numerous institutions worldwide. Rafik was honoured as a Member of the British Empire at Buckingham Palace for advocacy

in NHS Scotland which included minority communities.

His knowledge of medicine and public health structures is impressive. “My years of work in primary healthcare have taught me that the well-known concept of prevention is better than cure is truly at the heart of how we must approach healthcare,” Rafik says. “Also, the constant empowerment and support of front-line healthcare workers are just as important as the need for community engagement and participation. Higher education establishments must play a proactive role in this.”

A conversation with Rafik quickly shows that it is not only this noteworthy understanding of his field that commands respect. Apartheid has given him many reasons to be bitter and unforgiving, yet he chose to forgive and move forward. He really seizes life and every opportunity to make a difference and has played a proactive facilitating role in many healthcare initiatives worldwide.

A conversation with Rafik quickly shows that it is not only this noteworthy understanding of his field that commands respect. Apartheid has given him many reasons to be bitter and unforgiving, yet he chose to forgive and move forward. He really seizes life and every opportunity to make a difference and has played a proactive facilitating role in many healthcare initiatives worldwide.

Rafik and his wife, Rashida, moved back to the Lowveld in 2007. He loves this country’s people and the natural scenery which, according to him, “represent a huge evergreen garden of extreme beauty easily comparable with the natural scenes of Scotland, Canada and Switzerland”.

Although Rafik has lived abroad for over three decades, there is no place like home. “As South Africans we must remember that our strength as a nation lies most of all in embracing the diversity in ethnicity, religion and race,” he says. “A love of and celebration of this diversity should be the foundation of our society. A strong one will lead to unity, success and prosperity. We must realise that this does not only depend on politicians, but also requires commitment from young people who are, after all, our future.”

Text: LIEZEL LÜBENBURG. Photographer: JAMEEL AND HAMZA GARDEE