‘If you want a simple, fail-proof recipe for bread, look on any old flour packet. You won’t find it in A Book About Bread,’ says its author, master-baker and owner of the popular Glenwood Bakery, Adam Robinson. We stepped inside the heart of his home (the kitchen obviously) to learn more about the art of bread-making and managed to wangle a few recipes out of him too.

A veteran of the London restaurant scene who has lived in SA since 2003 Adam points out that cooking well, contrary to what most cook books or TV chefs will tell you, is ‘a devilishly complicated and wonderfully interesting mistress’. If you are already comfortable in the kitchen, or have at least dabbled in bread, you’ll find plenty to get your teeth into, as his book takes a deep-dive into dough, its making and baking.

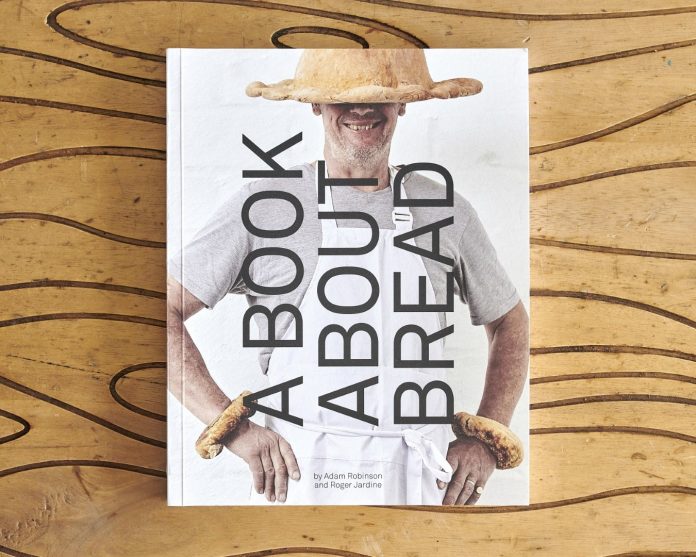

Adam teamed up with local photographer-designer Roger Jardine to produce this handsome volume, in which he cites a number of influences, particularly 16th century naturalist and physician Dr Thomas Muffett, as he breaks bread-making down to its essentials. You’ll learn about wheat and what makes flour good or otherwise…yeast, water, salt, baking and ovens all get their due. But it’s the dough, its handling and the microbiology of fermentation where the real magic happens, and Adam explains some of its mysteries in his idiosyncratic, often wry style.

Then he serves up 10 recipes, or formulas (as he styles them) – many of them Glenwood Bakery favourites. There’s a wholemeal sourdough and a lovely potato and rosemary bread, described as a gateway bread to the world of sourdoughs. There are also soft sourdough burger rolls, oat porridge sourdough and a ciabatta. The last is a favourite of Adam’s, and one of the reasons his bakery has become something of an institution or community hub, if you will, in Glenwood. All the formulas are accompanied by beautiful photographs, and as Adam describes good bakers as ‘anal’ there are precise listings of ingredients, times and temperatures and step-by-step instructions to help you get it right.

Having cooked in and run restaurants in England as well as France, Adam has a rich store of anecdotes that lend the book a nice light crumb, as well as a good understanding of what makes food and baking work. He flays the food industry in general and the mass-producers of bread in particular, and explains why most of the bread you get from the supermarket is so indigestible.

Happily though, Adam is no health-food nut. He’s almost as critical on this faddish topic, although he does touch on gluten intolerance and related themes in sensible terms. ‘I am not a fan of the science of nutrition and even less nutritionism, nor am I that interested in the health benefits of my work. It is about the taste.’

Amen to that!

Details: The book sells for R225, and is available from the Glenwood Bakery, at 398 Esther Roberts Road, Glenwood. To reserve a copy call 082 617 9768 or e-mail [email protected]. It is also available at African Root (Umhlanga), Hope Meats (Durban North), Surf Riders (South Beach), Humble Coffee (Morningside), Dukka (Morningside), KZNSA (Glenwood) and Parc (Glenwood). Online orders with deliveries nationwide can be placed through Bake-a-Ton or glenwoodbakery.co.za

Potato and Rosemary Bread

A comforting bread with a softer crust due to the dairy content. A gateway bread to the world of sourdoughs.

Ingredients

400g peeled potato

750g bread flour

2 sprigs rosemary

2g yeast (half a scant teaspoon)

130g barm

200g potato cooking water

200g milk or buttermilk or whey

20g salt

poppy seeds

Method

Roughly chop the potato and boil in unsalted water. When cooked, drain but keep the cooking water.

Let the potato cool to about 50°C and mash roughly. Mix with the rest of the ingredients until homogeneous. Do not knead. Tip it into a lightly oiled plastic container and leave for 20 minutes.

After the time lapse, return to it and fold. Repeat the folding twice more. After three hours of ‘bulk’ fermentation at 24°C, tip the dough onto your bench, divide into three even lumps. Firstly pre-shape your loaves by taking a corner and stretching it gently and folding back into the middle. Repeat this on seven sides, while rotating the loaf. Flip over and leave to rest seam side down.

After about 10 minutes, flip over again, stretch the ball away from you and gently roll the loaf onto itself, like a Swiss roll. Cup your hands around the loaf and gently pull it towards you, pressing the seam against your work surface to close the seam and tighten the outer surface. Place it on a floured cloth, seam side up, to rise. The cloth must be ‘ruched’ so that the loaves can be separated and rise in a shapely manner in their folds. When well proved, turn your loaves onto a floured board, seam side down, brush lightly with milk, sprinkle with poppy seeds and slash obliquely twice. Slide from your board onto your preheated oven tray or tiles. For this one, set your oven at about 200°C.

As indicated in the ingredients of this loaf, you can use milk, buttermilk or whey. I have used all three and prefer whey as it has the sugars of milk but not the fat. It really depends what you have lurking in your fridge. Milk is fine!

Instructions like ‘when well proved’ or ‘allow to double in size’, I find nebulous and unhelpful at best.

The bulk fermentation is for the flavour, but it is the combination of the proving and the oven kick that

will give you lightness. This is what we are aiming for. So a fully proven loaf is a dangerous thing as it can fall in on itself when loading into the oven. We are aiming for a springy consistency in your proving loaf – the springiness of a youth’s flesh while at rest. So not only will your loaf be well risen before loading but it will also kick while in the oven.

Remove from the oven after about 30 minutes. Your loaf is ready when it weighs 400g. Leave it to cool on a rack (not a flat surface) to allow the steam to escape.

Sourdough Burger Rolls

This formula makes a dozen rolls. The rolls are soft because of the milk content. Fat, in the form of butter, oil or milk, makes for soft breads. This has a particularly interesting flavour from the long interaction between the barm and milk, lending a distinct yoghurt taste to the rolls.

Ingredients

900g cake flour

650g milk

200g barm

20g salt

40g sugar

Method

This is stiffer than many of our doughs. Mix the ingredients and tip into a lightly oiled plastic container and leave for 20 minutes. After the time lapse, return to it and fold. Repeat this every 30 minutes three or four times. Then cover the dough and put it in the fridge, in the salad drawer, overnight for a long, slow fermentation.

Next morning, fold your dough one more time. Tip the dough onto a floured surface and divide into 150g lumps. Now flour your hands, but not the surface this time. Roll these lumps between the cupped palms of your hands and the work surface to form a homogeneous ball. Lay the balls onto a baking sheet with a 2cm gap between each roll. As they rise, they will touch and this will help keep them soft during the bake.

Preheat your oven to 180°C. When well risen (maybe three hours), brush with melted butter, sprinkle with sesame seeds and bake for 20 minutes.

Onion and Bay Bread

This bread, with its distinctive taste of bay and onions boiled in milk, reminds me of the bread sauce of my childhood – a thick relish that always accompanied a roast bird. It’s actually a mediaeval sauce, slightly sweet from the milk, spiced with clove and bay and thickened with day-old bread. Not many sauces in the European repertoire like that anymore. Try using this bread to make a roast chicken sandwich and you’ll understand.

Ingredients

420g milk

420g onion, peeled and chopped

4g bay leaves

150g wholemeal flour

600g bread flour

15g salt

2g yeast

220g barm

Method

Bring the onions, bay leaves and milk slowly to the boil. Simmer for two minutes and let cool to about 40°C. Remove the bay leaves and mix all the ingredients together to form a sloppy mass. Leave for

20 to 30 minutes and fold. Repeat this three or four times every 30 minutes. Aim for the dough to be at 24°C. I do not find an overnight fermentation improves this dough much. A three-hour bulk fermentation is fine.

Divide your dough into three lumps. First, pre-shape your loaves by taking a corner and stretching it gently and folding back into the middle. Repeat this on seven sides while rotating the loaf. Flip over; squeeze the seam shut with the side of your hands. Leave to rest seam side down. After about 10 minutes, flip over again, stretch the side of the ball nearest you towards you and fold over the loaf, then the right side away from the middle and fold back over two-thirds of the loaf. Do this with the left side and again with the top. Flip the loaf over. Cup your hands around the loaf and pull it towards you, pressing the seam against your work surface to close the seam and tighten the outer surface. Put it seam side up into a basket that has been lined with a floured cloth.

Set your oven to 220°C. After about an hour the dough should have proved sufficiently. It will be particularly active from the warmth of the onion/milk mixture and the sugars present in the milk. Turn the dough onto a floured wooden board or pizza paddle, seam side down. Slash boldly, insert half a bay leaf into each slash and slide onto your preheated oven tray or tiles. Spray the oven and spray again in four or five minutes, to inhibit the formation of a crust and encourage a greater oven kick. Spray the oven, not the loaf. You are trying to create steam. Spraying directly onto the loaf will give you a blotchy crust.

Remove from the oven after about 30 minutes. Your loaf is ready when it weighs 500g. Leave it to cool on a rack (not a flat surface) to allow the steam to escape.

Hot Cross Buns and Easter (maybe in a side bar to separate)

You don’t need to scratch the surface of our Easter traditions very deeply to realize that it is a spring pagan festival laced with symbols of fertility and growth. Before spring, we have to have a time of dearth – lent. When lent ends we have celebration, parades and enriched foods, culminating in our pascal lamb on Easter Sunday. Thus enriched, sweetened breads or special cakes grace many European Easter week traditions. The hot cross bun, does, though, seem to be peculiarly English, originating in maybe the 14th century. It is a bun with some powerful magic, particularly the batch baked on Good Friday. Taken on your ship, it protects against shipwrecks and a morsel will help the ill heal. Our modern recipe comes from the end of the 18th Century and is a sourdough bun.

Makes 12 90 gm buns

The buns

150g raisins soaked in boiling water for 30 minutes

25g dried citrus peel, chopped

450g flour

125g sourdough mother culture

1 teaspoons salt

3 teaspoons mixed spice

75g melted butter

80g sugar

1 egg

215g water

Grated zest of 1 lemon

Crosses

125g milk

115g flour

salt

Method

Mix all the bun ingredients and tip it into a lightly oiled plastic container. Leave for 20 minutes. Do not knead. After the time lapse, return to it and fold it.

To fold the dough you put your well wetted hands underneath one of the four corners of the dough, lift this corner to stretch it and deposit your stretched corner on to its opposite side. This should be repeated for the other three corners. If a wet dough, you might need to use a plastic scraper to incorporate the bits of flour from the edges of your container back into the bulk of the dough. Try to make sure that there are no lumps and that you have a homogenous mass. Repeat this every 30 minutes three or four times. You will end up with a transformed, sleek homogenous mass. Cover the dough and put it in the fridge overnight for a long, slow fermentation.

Next morning, fold your dough as above one more time. Tip the dough out on to a floured surface and divide into 90g lumps. Now flour your hands, but not the surface. Roll these lumps between the cupped palms of your hands and the work surface to form a smooth ball. Lay the balls on to a baking sheet with a 2 cm gap between each roll. As they rise, they will touch and this will help keep them soft. Pre-heat your oven to 180°C. When well risen (maybe 2 to 3 hours), mix your cross ingredients and pipe gently onto your well risen buns. Bake for about 20 minutes.

Eat with butter and thoughts of the road to Calvary!

Image credit: Roger Jardine.